In the last twenty years, the idea of addiction and the brain disease model - in other words, the concept that addiction is a disease - has soared in popularity.

It is supported by many respected individuals and organizations. For example, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) currently defines addiction as “a chronic and relapsing brain disease.”

Similarly, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) calls addiction “a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry.”

But does that mean that the millions of Americans who struggle with addiction cannot recover fully?

Do these definitions encompass the true nature of addiction, or is there more to the story?

Could it be that it’s time to update our understanding of whether addiction is a disease, as well as the brain disease model itself?

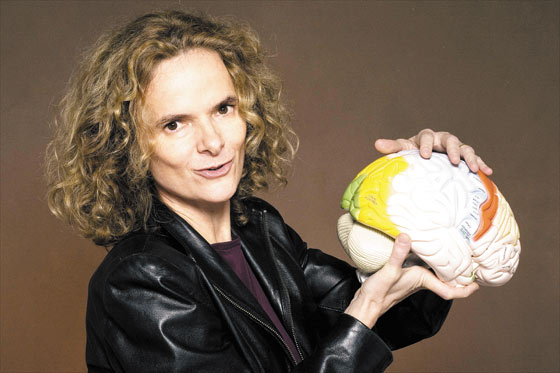

To answer these questions, we spoke with expert psychiatrist, author, Yale lecturer and American Enterprise Institute (AEI) Scholar Dr. Sally Satel.

About Dr. Sally Satel

Dr. Sally Satel is a practicing psychiatrist and lecturer at the Yale University School of Medicine. She examines mental health policy and political trends in medicine.

Dr. Sally Satel is a practicing psychiatrist and lecturer at the Yale University School of Medicine. She examines mental health policy and political trends in medicine.

She's the author of several books, and in this interview we'll be talking about her latest book Brainwashed: The Seductive Appeal of Mindless Neuroscience, which she co-authored with psychologist Scott O. Lilienfeld.

Brainwashed was a 2014 finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Science.

In her spare time, Sally also volunteers at a methadone clinic.

The Fallacy of the Addiction Disease Model

In our interview, Dr. Satel discussed …

- The origins of the brain disease model of addiction

- The changes in the brain that accompany addiction and what distinguishes addiction from other neurological disorders

- An empowering way to look at addiction and personal agency

- The importance of asking deeper questions and addressing the underlying core mental and emotional health issues that drive substance abuse

- How depression and anxiety connect to addiction

- How your sense of shame might be trying to help you recover

- What loved ones can do to support - not enable - those struggling with addiction

- The role of medication in detox and addiction treatment

Transcript of "Is Addiction a Disease?" Video Interview with Dr. Sally Satel

= = = = =

Dr. Sally Satel: Thank you for asking me [to do the interview]. I just want to clarify something right at the beginning. It's funny you call me an activist. People rarely do. But they have and I say, "I'm not an activist, I'm a reactivist."

I think of an activist as someone who actually doesn't look at the data, but is really driven by ideology. And in our book, Scott and I certainly wanted to do that.

But I'm a reactivist because I think that the brain disease model … has not been the most constructive development in this field.

The Origins of the Disease Model of Addiction

Caroline McGraw: Well, thank you. I think that's a great clarification and a really good jumping off point for the first question. Because in your book you do a great job of arguing for revisions for the current model of addiction. So before we dive into that, could you just fill our listeners in if they're not familiar, what is the prevailing model? What is the brain disease model?

Dr. Sally Satel: Well the formulation of disease model of addiction (as a brain disease) was actually first introduced in 1995. I distinctly remember the then director of NIDA, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, whose name was Alan Leshner. He was a psychologist. And he introduced it at a meeting that was sponsored by the National Institute of Health.

And I thought that's a very strange way to think about it. I mean certainly drugs affect the brain, why would people take them otherwise? And there's no question that they cause changes in the brain.

And I thought that's a very strange way to think about it. I mean certainly drugs affect the brain, why would people take them otherwise? And there's no question that they cause changes in the brain.

Which, if you ask Dr. Leshner, “What do you mean by it's a brain disease?”, that's what he would say. Because drugs change the brain. Of course as an aside when you think about that it's not very satisfying, because everything changes the brain. I mean, this conversation will change our brains, and people listening to it.

Now granted, not all brain changes are the same, and we'll get back to that in a minute. But anyway, he said it was a brain disease. And I know that,of course addiction and alcoholism have been considered diseases probably ever since Benjamin Rush. Or at least he introduced that over two centuries ago. But even then it had a kind of a metaphoric quality. I mean, certainly it's a form of behavioral pathology. How could it be healthy to constantly sabotage yourself, and injure your body, and risk overdose? That's not a healthy way to live. And in psychiatry we can certainly consider it a disorder of behavior.

So the disease part didn't bother me so much. It only bothers me when people invoke it as a reason why they do what they do. In other words, they have no control and they can't do otherwise. And that is not the most constructive use of disease in this context.

But if that's a reason a person finally got through to someone—this is why I really need help, hence why I have to do these things—then I’m totally fine with it. I would never debate a patient, someone who was working towards getting better, how they think about their problem if it ended up being constructive for them.

But the brain disease thing took it into a whole other realm. And it made it essentially interchangeable with schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis.

And there's a big difference between the brain changes of let's say Alzheimer's disease and addiction. I think it should be obvious but let me just illustrate. And I'll illustrate with actually a case of our former drug czar Michael Botticelli, who's a lovely man. I met him, everyone loves him and I can see why.

Michael was a big champion of the brain disease model.

And it turned out, and he's been very public about this, he was an alcoholic at one time. I think he's been clean, in recovery, for over 20 years. And he was driving erratically on the Mass Turnpike. And I think he got in an accident, although thank God no one was hurt or killed.

But he got arrested for drunk driving. And the judge told him, you can do two things. You can go to jail because that's what we often do with people who drive drunk. But I imagine he had a good record previously so the judge was really quite generous, and gave him the option of getting clean, basically. Go to a treatment program, you do what you have to do, just you're gonna have to get clean and we're gonna make sure of that.

And so Mr. Botticelli with his brain disease said, "Well wow. Thank you for giving me this choice and I choose treatment." And I believe he actually went to AA. The way he phrased it, he said he went to a church basement and then went to AA, and has done well since.

So if you take the addiction brain disease notion to its extreme and analogizing it to Alzheimer's disease, which its proponents sometimes do, then no matter what kind of options a person gives you, it's not going to change.

But we know change does in fact happen under the right circumstances and options for people with addiction.

But with other brain diseases, these options don't work to alleviate the disease.

If Addiction is a Disease, Can You Be Held Accountable?

For example, if your memory deteriorates any further and someone tells you that you're gonna have to go to jail, or if you can keep it from deteriorating we'll give you a million dollars ...these options unfortunately don't change the memory deterioration. It doesn't work that way.

Because the changes in the brain that accompany addiction do not prevent the person from responding to meaningful consequences, be they incentives or sanctions. And that's a key difference.

If Addiction is a Disease, Can You Be Held Accountable?

Caroline McGraw: I really like that. Yes. You have a great line in the book, that you talk about, "Addiction involves both biological alterations to the brain and deficits in personal agency." So it's not either or, it's both/and.

Dr. Sally Satel: No. And actually ... unless you're a Cartesian dualist, I mean everything is in the brain, of course. We wouldn't be having this conversation if our brains weren't working. But at that point it becomes trivially true. Of course it's all about the brain.

So some people will say that. I've actually had some people say, "Well, even when you're in treatment and you're doing relapse prevention therapy, it's in the brain." I say, "Well of course it's in the brain! Everything's in the brain!" At that level it doesn't really mean much anymore.

But when you're going to talk about brain disease as a reason why a person frankly should not be held accountable ... And I don't mean punishment in any kind of a “lock him up” sense. That's not what we're talking about.

We're talking about shaping behavior in the direction of recovery and being functional, and reuniting with your family and your community, and feeling purposeful in life and content and all that. Sure your brain's gonna play a role in all that too.

But again, a highly mechanistic explanation of addiction doesn't lead you to think that way. It doesn't even lead you to ask questions like,

"Well why did you become an addict?" That's a meaningful question. Why did a person become an addict? Would you ever say to someone, "Why did you become an Alzheimer’s patient?"

I mean of course some day we will probably be able to explain the pathology of it. And I hope they do it quick because that's a devastating illness.

And that - what Scott (co-author Scott Liliienfeld) and I would call the neurocentric approach to Alzheimer's - is exactly where we want to be!

Because the tissue damage, the circuitry deterioration, and so on in Alzheimer's, is only going to be fixed by working on the brain.

But in addiction, not that much is fixed by directly working and intervening at the level of the brain. And even the medications we have when you think about it … and I'm all for them, I work in a methadone clinic.

There's nothing I've ruled out. If anyone wants to go to AA, great if that works for them. If they want to take methadone, fantastic. They want to stop on their own, which a lot of people actually do but we don't hear about them very often because they stopped on their own. They're not people who come into research programs, they're not people who come into treatment centers, so they don't get counted. But they can stop on their own.

Conditions and the Addiction Disease Model

Caroline McGraw: In the introduction to Chapter 3 you talk about these studies that many people forget, of the US soldiers who went to Vietnam and they were using drugs. And then they came home and they stopped. And this is a narrative we don't hear as much. This idea that, under the right conditions recovery is not just possible, but it's even probable, that people recover.

Dr. Sally Satel: Yes. And you used a key phrase which is "under the right conditions."

And look, a lot of people are under terrible conditions.

All their friends use.

Their communities, especially hearing so much now of the opioid crisis, these economically ravaged places ...

There's no hope, there are no jobs, painkillers and heroin are highly accessible, it's virtually normalized, everyone else is using it.

I mean, it takes a lot for someone under those circumstances to pull out of it. I understand that.

But part of the goal of treatment is to change the circumstances.

But part of the goal of treatment is to change the circumstances.

And until there's an economic recovery in these places, unfortunately that kind of a solution ... is not around the corner. But there probably are more creative things that can be done at the local level than we imagine.

And hopefully they're going on right now in places, in Kentucky and Ohio and Maine and all this.

But it is an incredibly big challenge because in a way you're talking about addicted communities. And that is hard. But when we talk about addicted individuals, let's say the person who appears to have everything.

Just go to Hollywood and you'll find very talented, very smart, very wealthy people, who still struggle with drugs and alcohol.

It does make sense to ask why. "Why are you having these problems?" And you'll usually get a psychological answer of sorts.

Everything from depression ... sometimes it's clinical depression, sometimes it's clinical anxiety. In which case, me as a psychiatrist, I kind of think, oh great! Because we actually have medication for that.

Caroline McGraw: We can help you.

Dr. Sally Satel: Yes. Sometimes it's a little more existential.

These pervasive feelings of loneliness and aimlessness and desolation and never feeling comfortable in your skin. And that's harder to work with but you can. You definitely can.

Caroline McGraw: Yes. Predominantly, the Participants that come through our program are dealing with dual diagnosis. They're dealing with a diagnosed mental health concern and the substance abuse.

And so I loved this line in your book: "The paradox at the heart of addiction is this: How can the capacity for choice coexist with self-destructiveness?"

That's what we see so much in our program. You have these smart, capable, amazing, like you were talking about, individuals who seem to have it all. And you're thinking, “Why are you self-destructing?”

Dr. Sally Satel: Right.

Disease Model of Addiction

Caroline McGraw: And that's the time where you, or I should say we, really try and delve into those underlying core issues, and address those psychological concerns that you were talking about.

Dr. Sally Satel: Right, right. And when you quoted that it reminded me - it may even be in the same paragraph I'm not sure - of one of the stock phrases of Dr. Nora Volkow.

Now she's the head of NIDA and has been a very very vocal promoter of the brain disease concept - the disease model of addiction. And she's fundamentally a neuroscientist, as opposed to a clinician. I think that's fair to say.

Dr. Nora Volkow

And so what she likes to say is, "I've never met anyone who wanted to be an addict."

Well, I don't know, I haven't either.

And I've never met anyone who wanted to be overweight or poor. I mean these are circumstances that come about incrementally. And they're not the goal that people are seeking.

No one wants to be fat. No one wants to gamble away their life savings. But what they want is immediate relief. And that relief, they get it in the short term. And then of course, there's fallout.

And then you've kind of get two layers of problem. One, that layer that generated the motivation to use, and then all the fallout of your using for years. You've alienated your family and your boss, and you didn't finish your education. Then it even compounds your stress and you could see more reason to continue to use. So it's a terribly vicious cycle.

Download E-Book Healing Core Issues

Shame and Guilt in Addiction

Caroline McGraw: Exactly. I love how you said that. There are layers on top of layers. There's what you started out with, then there's the dysfunctional behavior, the shame, all this stuff surrounding the addiction, that was to try and cope with the dysfunctional issue or psychological trauma or whatever else you have.

Dr. Sally Satel: Yes. But you know shame is an interesting thing.

And I actually think, when I have patients say that to me that they were ashamed, I think that's healthy. I say, "Well, thank God!" Your sense of right and wrong is still working. It doesn't mean that any clinician should ever make a person feel worse, or scold them in any way, or make them feel ashamed. People feel bad enough.

But the fact that they do is not something I try and say, "Oh don't feel bad!" No, that's healthy! And so what are we going do to get the trust back, with your family and your kids and this kind of thing. But you're also right that it can be a spur to continue to use.

And that's where it's not constructive.

Caroline McGraw: That's really helpful though. I like that. Almost, people feeling ashamed that they have so much shame. But you're kind of reframing it as,“No, this is a sign that you have some health here and some discernment, almost.”

Dr. Sally Satel: Yes, I think so. And I never had anyone look at me and say, "What?!"

You know they say, "Oh, yeah." You know you don't want to offend anyone. But I don't believe I've offended anyone yet. And they seem to think that's a valid point.

Caroline McGraw: It is, it is. Because something that kind of boggles the minds of our Participants ... is this whole idea that what we have inside of us, our emotions and everything, are trying to teach us and they're trying to show us something. And so I like this idea that the shame is trying to bring you to your own attention.

Dr. Sally Satel: Yes. That's a nice way to put it.

Caroline McGraw: Thank you. Well going back to, you mentioned loved ones, family members, the ripple effect of addiction. And I liked how, in your book, you talked about the importance of natural consequences. And how often, loved ones will try and shield people from the natural consequences of their using. So, I know there are a lot of loved ones and family members listening. So, could you offer more on that? Any suggestions? Any guidance there?

Dr. Sally Satel: (Laughs) What I remember writing is that, it's the loved ones that often pressure them into coming in.

I haven't seen the literature on intervention so I don't know about those. But they go from subtle - your wife gives you a look when you've missed your kid ball game - to your wife leaves you. But most people come in because something's falling apart. And more often than not it's someone else who's really calling their attention to it.

So I think that these consequences, and the fact that people see other people becoming disappointed in them, are very motivating.

Now it's true that there are all these various ramps at which people get off.

Some people just get off the ramp of drug use to recovery because their wife gave them a dirty look, or their kid said, "Dad, you missed my game again!" And that's devastating to people.

Other people go a long way down before they get off. And there are always some people that just never do. But there's a bit of mystery to that.

Some of it is also that the conditions, as you say, aren't quite right yet. And also I think sometimes it shows also how difficult ... I think this is why people are so ambivalent about giving up their drugs.

Because they're not ready to face life without some numbing, you know?

Caroline McGraw: Yes.

Dr. Sally Satel: And as we alluded to before, the further down you are in that spiral, the more numbing you almost feel you need. So again a vicious cycle.

Caroline McGraw: That makes so much sense. And I also liked how at the end of Chapter 3, you redefine addiction outside of the brain disease model. And I was wondering if you could share that revised definition that you have come to through you research.

Dr. Sally Satel: You know Caroline, could you read it to me?

Why Addiction is Not a Disease

Caroline McGraw: Absolutely. I have it bookmarked. "In the end, the most useful definition of addiction is a descriptive one such as this: Addiction is a behavior marked by repeated use, despite destructive consequences, and by difficulty quitting, notwithstanding of the user's resolution to do so."

Dr. Sally Satel: I suppose if someone held a gun to my head and said, "Well if it's not a brain disease what kind of a disease is it?"

Then I suppose, if this were my choice, pick one or die, I'd say it's a behavioral condition. Because unless somebody acts a certain way you'd never call them an addict.

But Scott (co-author Scott Lilienfeld) and I really tried to get away from the, "It's a brain disease! It's not a brain disease!"

But Scott (co-author Scott Lilienfeld) and I really tried to get away from the, "It's a brain disease! It's not a brain disease!"

And to focus more on levels of analysis, or explanatory frameworks.

And our thing is that it's just not that constructive to call it a brain disease.

Because you're focusing too much on the level that is just a small part of the whole process.

In fact, I think calling addiction a brain disease is a great disservice to an extremely complicated set of behaviors. To me it's fundamentally a human drama.

So we like to talk about that that's a neurocentric view, that looking at the brain is the most powerful way to explain it.

Well if you're a neuroscientist, if you're a dopamine biologist, it probably is.

But if you're a person who wants to get better, a family member who wants you to get better, a treatment provider who's there to help you get better, a policymaker who wants to make the best policy, that's not the level.

It's more at the level of behavioral and psychological and even environmental factors.

It's really a matter of emphasis. And that's the point we really wanted to make.

The Limits of Addiction Medications

Even when you look at medications ... Maybe I sound like I'm splitting hairs here, but I don't even think they're treating addiction so much.

Take methadone, that treats withdrawal. And to some extent it suppresses craving. So it's highly stabilizing for people. And there are some people, I think the minority, but there are some people who continue to use opioids largely because they cannot tolerate the withdrawal.

For people like them, these replacement medications should be the greatest thing in the world.

For people like them, these replacement medications should be the greatest thing in the world.

And for some they probably are.

But then you'd ask well, "Why are so many people in our methadone clinics still using heroin?"

Granted a much lower level than they were before. "Why are they using cocaine? Why are they drinking?"

Because it wasn't just about the withdrawal. There are other things driving their drug use. And then buprenorphine same thing. And then there's Vivitrol, which is an injectable naltrexone, which is a blocker. And so I support everything. Let a thousand flowers bloom.

But anyway, but even some of the brain disease proponents like to talk about the medications that they've helped generate. Well all these medications existed before we had the first brain scanner.

Which isn't to say that ... You know, maybe one day there will be more effective medications developed. I'm personally kind of skeptical that medication will ever be a major answer to this problem. But I think it can help a lot for certain people.

I like to tell young people that if they get on methadone or buprenorphine, don't look at it like it's their life's duty to stay on it.

In our clinic, which is inner city Washington D.C., the average age is 57. So these are hardcore, old school addicts. They started with heroin.

Nowadays most people start with pills. They've been in and out of programs forever. And a number of them have decided, and I think wisely, it's like hey, for some reason I can't get off this.

Or every time I do, bad things happen. So they just stay on it. And they'll probably stay on it forever. And that's fine, because that's the responsible thing to do. But if you're a young person, you should really look at those medications as a temporary kind of aid.

Caroline McGraw: That makes total sense. This can be a bridge to where you want to go but it's not the end destination.

Dr. Sally Satel: Right.

Incentives for the Disease Model of Addiction

Caroline McGraw: And you also talk about in your book, this idea that, one of the current advantages to the brain disease model has been getting additional funding for addiction research because it's been framed this way. But of course, one of the major drawbacks is that it downplays personal agency and it's not complete picture. So, could you say more about that?

Dr. Sally Satel: You know I do acknowledge that there are good sentiments behind the disease model of addiction ...

Right, to get more research funding.

Because in 1995, Harold Varmus was the head of NIH.

Because in 1995, Harold Varmus was the head of NIH.

And independent of Harold Varmus, who's a brilliant oncology researcher ... I believe he has a Nobel Prize ...You know NIH is a biomedical institution.

So I could see why there was such an effort to make addiction seem like a neurological problem. And again it has those elements. There's no question about it.

But right, the idea was to get more funding within NIH, and to I think secondarily get more treatment funding. And some people emphasized the highly reductive model of addiction to kind of move cultural responses away from punishment to treatment. And all that's great. Whether it did any of those things, I honestly don't know. I mean we had a huge crack problem … you could come up with a million other reasons why there was more research funding. And there was. So it's hard to know.

But you know if it helped, I'd say that was a positive outcome. But I think it's based on a deep conceptual confusion. And I always think it's better to be clear thinking, even if there are no implications.

But in this case, the implications to me are tremendous. Because unless you have a realistic view of the nature of addiction, you're not going to come up with good policies and treatment programs.

Caroline McGraw: Exactly. Exactly. Could not have said that better. And I want to honor your time, and I'm so glad you were able to be with us. So just to wrap up, is there any final points you want to share? Or encouragement for folks who are dealing with addiction? Any closing words.

Dr. Sally Satel: I suppose my suggestion is just don't get too caught up in slogans and models and this and that.

Just know that people have come before you.

A lot of people have stopped.

Most people actually have stopped.

And many have actually stopped on their own.

Obviously you're in a program now so that didn't work out. But it should be encouraging to anyone that this is certainly possible.

And have things in your life, work towards things in your life that you don't want to lose. Because once you have them you probably won't risk them. And that's one of the very important ways to stay clean and move on. And I wish you the best.

Caroline McGraw: Thank you so much.

Download Dual Diagnosis Free EBook